I have made so many photographs in my life that the number loses its edges. Tens of thousands, maybe more, each one a small decision to notice, to frame, to say this mattered enough to stop time for it. If I gather the hours I spent in the darkroom—standing, waiting, breathing the chemical tang of fixer and developer, hands stained into permanence—they would accumulate into months. Entire seasons lived under safelight. Months of my life spent coaxing what was invisible into an image, persuading light to confess what it had touched.

In the darkroom, the delicate becomes formidable. The sun, which burns and vanishes so quickly in the open world, learns to stay. Light that once slipped through asked to hold still, to endure darkness long enough to be seen. I mixed solutions like a kind of prayer—measure, pour, stir, wait—knowing that precision mattered but so did patience. Too long and the image would drown into a fog. Too short and it would remain a ghost. I learned that photographs are not taken; they are negotiated.

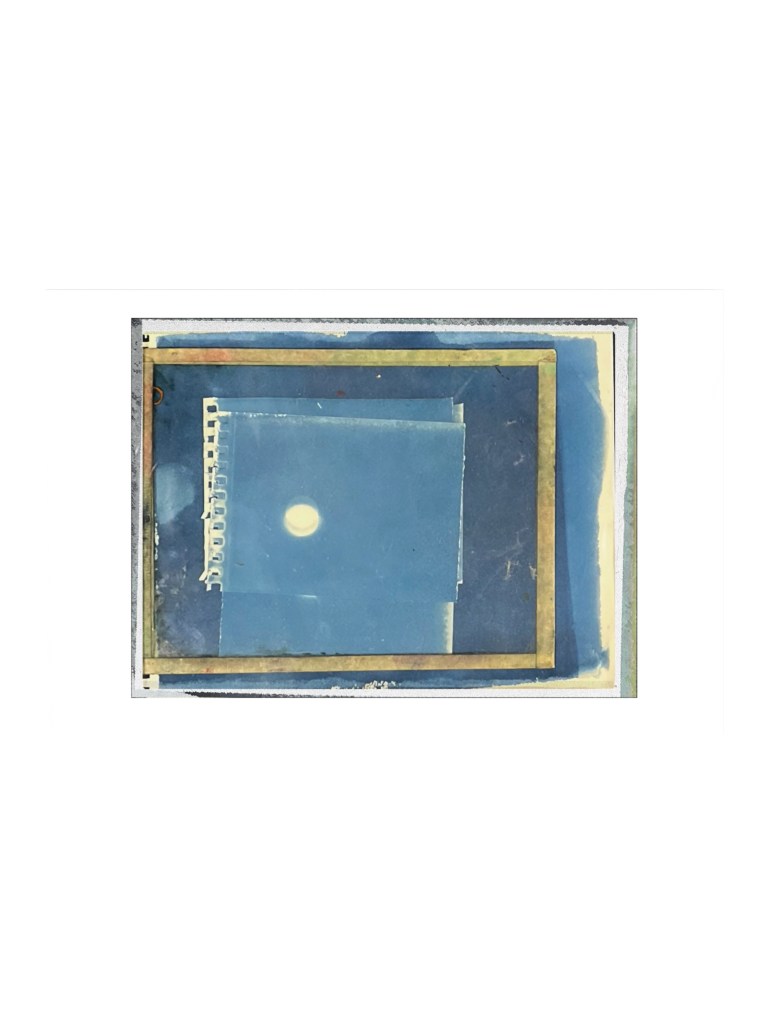

I watched images appear the way language does when you finally find the right word. Slowly, reluctantly, as if unsure they wanted to exist. A pale suggestion first, then it materializes. I learned to trust that what I could not yet see was still there, suspended in silver halides, waiting for the right conditions to reveal itself. Faith—not from doctrine, but from trays of liquid in the dark.

I spent hours bent over microscopes, studying the grain of silver, those constellations of chance that hold an image together. Focusing and unfocusing, discovering that sharpness is not the same as clarity. The grain taught me humility. No matter how carefully I exposed the frame, there was always randomness, always something beyond control. The image was never only mine. It was the result of light, chemistry, time, and my own imperfect hands. Creation was collaboration.

After all of this—after enlargers and meters and lenses heavy as declarations—I stepped into a camera obscura. I did not know yet what I was seeing, only that the world had entered a room and laid itself gently across the walls. The ocean was toward the ceiling. People floated upside down. Clouds drifted, silent and astonished, across plaster. The image moved without my permission. It breathed. It did not need to be captured to be real. The world wants to be seen, and I stepped into a camera.

I stood there, inside that quiet miracle, watching light translate itself without effort. No shutter, no film, no chemicals. Just a small opening and patience—stay long enough for my eyes to adjust. The image was fragile, temporary, already disappearing as soon as I noticed it, and yet it felt complete. Whole. I remember thinking that seeing could be an act of receiving rather than taking. Still, I chased mastery. I carried gear that weighed as much as certainty. Cameras that promised precision, lenses that bent the world obediently. I believed that if I owned the right equipment, I would finally deserve the images I loved. I measured myself in stops and focal lengths, in sharpness charts and brand names. I confused complexity with depth, control with devotion.

But every photograph I loved most came from something quieter. A moment when I forgot the camera and remembered my own attention. A frame guided not by settings but by longing. What I was really trying to preserve was not light, but feeling—the ache of noticing, the tenderness of attention. The equipment was never the source. It was only a conduit.

Now I understand that the darkroom was teaching me something else all along. That what develops in darkness comes from what you carry into it. That love is the most reactive element. That the image appears when you are willing to wait with it, to trust that something meaningful is forming even when you cannot yet see it.

I never needed all that gear. I needed my eyes, yes—but more than that, I needed my willingness to care. The photographs were never inside the camera. They came out of me, out of my attention, my patience, my desire to witness. Light only agreed because it recognized itself there.

I am still making images. Even now, without trays or timers or microscopes, I am developing them—no from a camera, exactly, but from inside myself, slowly and lovingly—letting what I love become visible in the dark.

Leave a comment